The role of AI in BCI development

In the exciting world of neuroscience, the collaboration of BCI technology with AI steers in a promising phase of expansion and development. At Nexstem, we are at the forefront of this revolution.

In the exciting world of neuroscience, the collaboration of Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) technology with Artificial Intelligence (AI) steers in a promising phase of expansion and development. At Nexstem, we are at the forefront of this revolution, leveraging cutting-edge hardware and software to unlock the full potential of BCI systems. Let's take a journey as we delve into how AI is changing the landscape of BCI technology and the remarkable impact it holds for the destiny of neuroscience.

Introduction to BCI and AI

A Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) is a technology that facilitates direct communication between the brain and external devices, allowing for control or interaction without needing physical movement. In contrast, AI boosts devices to gain knowledge from data, adjust to new information, and carry out tasks smartly. When combined, BCI and AI chart a course for ground-breaking applications that revolutionize the interaction between humans and machines.

Integrating AI into BCI System

AI-based methods including machine learning, deep learning, and neural networks have been thoroughly blended into BCI systems, ramping up their utility, effectiveness, and user-friendliness. The power of AI algorithms allows BCI systems to decode intricate brain signals, cater to individual user needs, and fine-tune system engagements on the fly.

One such example is the combination of machine learning algorithms, particularly deep learning methods, with EEG-based BCIs for motor imagery tasks.

Motor imagery involves imagining the movement of body parts without physically executing them. EEG signals recorded during motor imagery tasks contain patterns that correspond to different imagined movements, such as moving the left or right hand. By training deep learning models, such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs) or recurrent neural networks (RNNs), with large datasets of EEG recordings from motor imagery experiments, researchers can develop highly accurate classification algorithms capable of decoding these intricate brain signals.

For instance, studies have shown that CNNs trained on EEG data can achieve remarkable accuracy in classifying motor imagery tasks, enabling precise control of BCI-driven devices like prosthetic limbs or computer cursors. Furthermore, incorporating techniques like transfer learning, where pre-trained CNN models are fine-tuned on smaller, task-specific datasets, can facilitate the adaptation of BCI systems to individual user preferences and neurophysiological characteristics.

Moreover, advancements in reinforcement learning algorithms offer opportunities to dynamically adjust BCI parameters based on real-time feedback from users. By continuously learning and adapting to user behavior, reinforcement learning-based BCI systems can optimize system engagements on the fly, enhancing user experience and performance over time.

Signal Processing and Analysis

Artificial Intelligence is instrumental in the world of signal processing and analysis when it comes to Brain-Computer Interface systems. It uses cutting-edge algorithms for specific feature extraction, sorting brain signals, and removing unnecessary noise, all of which make the data collected more accurate and trustworthy. These data yield critical understanding about brain functioning, opening doors for myriad applications.

Specific algorithms are commonly employed for various tasks in signal processing, particularly in feature extraction.

Feature Extraction Algorithms

Advanced signal processing algorithms such as Common Spatial Patterns (CSP), Time-Frequency Analysis (TFA), and Independent Component Analysis (ICA) are extensively utilized for precise feature extraction in BCI systems. These algorithms are specifically designed to identify and extract relevant patterns in brain signals associated with specific mental tasks or intentions.

Noise Reduction Techniques

Despite their effectiveness, BCI systems often encounter various types of noise, including electrical interference, muscle activity artifacts, and environmental factors. To ensure the integrity of neural signals, sophisticated noise reduction techniques are employed.

Types of Noise and Mitigation Techniques

Electrical Interference: Adaptive filtering techniques are employed to suppress electrical interference from surrounding equipment.

Muscle Activity Artifacts: Artifact removal algorithms, such as Independent Component Analysis (ICA), are utilized to eliminate muscle activity artifacts from the recorded signals.

Environmental Factors: Spatial filtering methods like Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) are implemented to mitigate the impact of environmental noise.

Ensuring Data Quality

These noise reduction techniques are crucial for maintaining the quality and reliability of the collected data, ensuring that it is suitable for subsequent analysis and interpretation. By effectively suppressing unwanted noise, BCI systems can provide accurate and trustworthy data for various applications.

Adaptive and Intelligent Interfaces

The role of AI is crucial in creating intelligent and customizable interfaces for BCI systems. It ensures a personalized, responsive, and predictive modeling based on user habits. These interfaces significantly improve user involvement, productivity, and satisfaction in numerous applications.

Let's delve into a case study that exemplifies the fusion of AI and BCI technology

Primary Technology

The Crown, a specialized EEG headset, focuses on BCIs employing EEG technology for real-time cognitive state monitoring and interaction.

Use Case(s)

The Crown utilizes machine learning algorithms to interpret EEG data, providing actionable metrics on cognitive states such as focus and emotional well-being. Designed for both consumers and developers, it interfaces with various platforms, serving diverse use cases from productivity enhancement to research.

Example Experiences

1. Music Shift

Music Shift utilizes The Crown's EEG capabilities to measure the brain's response to music, identifying songs that enhance concentration. The app connects with Spotify Premium accounts to curate playlists that maintain focus and promote a flow state.

2. Mind-controlled Dino game (Created by Charlie Gerard)

This project leverages The Crown to train specific thoughts, like tapping the right foot, to control actions in Chrome's Dino game. By interpreting EEG signals, users can interact with the game solely through their brain activity.

3. Brain-controlled Coffee Machine (Created by Wassim Chegham)

Using the Notion 2 headset, this project detects thoughts of moving the left index finger, triggering a coffee machine to brew and serve an Espresso via Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE). The integration of BCI technology allows users to control devices through their brain signals, enhancing convenience and accessibility.

In summary, The Crown exemplifies the integration of AI and BCI technology to create adaptive and intelligent interfaces. By leveraging machine learning algorithms and EEG technology, it enables a range of innovative experiences, from enhancing concentration with personalized music playlists to controlling devices through brain signals, ultimately improving user engagement and satisfaction.

Enhanced User Experience

BCI systems powered by AI play a vital role in augmenting user interaction by offering intuitive controls, minimizing mental burden, and encouraging more natural paradigms of interaction. Users can effortlessly undertake complex tasks and liaise with external devices, paving the way for a mutually beneficial partnership between humans and machines.

For instance, one example of intuitive controls is brain-controlled cursors, where users can move a cursor on a screen simply by imagining the movement of their limbs. This approach eliminates the need for traditional input devices like mice or touchpads, reducing physical effort and cognitive load for users.

Another intuitive control mechanism is the use of predictive typing interfaces, where AI algorithms analyze users' brain signals to anticipate their intended words or phrases. By predicting users' inputs, these interfaces can speed up the typing process and alleviate the cognitive burden associated with manual typing, particularly for individuals with motor impairments.

Furthermore, gesture recognition systems, integrated with AI algorithms, enable users to control devices through natural hand movements or gestures detected by wearable sensors. By translating hand gestures into commands, these systems offer a more intuitive and expressive means of interaction, resembling natural human communication.

Improving Performance and Accuracy

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is essential in enhancing the efficiency and precision of Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) systems by leading the progress in decoding algorithms, error rectification methods, and adaptive learning models. By ceaselessly learning from user responses and refining the dissection of data, AI endows BCIs to attain unparalleled degrees of detail and dependability.

Applications in Healthcare and Rehabilitation

Healthcare and rehabilitation procedures are being revolutionized by AI-enhanced BCI systems. This shift encompasses assistive technology, neurorehabilitation, and the diagnosis of brain-related conditions. These systems present innovative methods for enhancing health results and standard of living, laying a foundation for individualized and evidence-based strategies

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite AI's enormous promise in BCI creation, there are still periods of difficulty yet to be navigated, encompassing issues like the acquisition and utilization of brain data, comprehension capabilities, and ethical questions. One of the main challenges lies in the availability and quality of brain data required for training AI algorithms in BCI systems. Access to large, diverse, and well-curated datasets is essential for developing accurate and robust models capable of decoding complex brain signals effectively.

Furthermore, ethical considerations surrounding the collection, storage, and usage of brain data present significant challenges in the field of AI-powered BCIs. Safeguarding user privacy, ensuring informed consent, and addressing concerns related to data security and potential misuse are paramount. The ethical implications of BCI technology extend beyond individual privacy to broader societal concerns, including the potential for discrimination, surveillance, and unintended consequences.

Tackling these hurdles and outlining the path ahead for exploration, as well as innovation, is crucial for unlocking the comprehensive potential of AI-powered BCI systems and progressing within the neuroscience domain. Addressing the challenges of brain data acquisition and ethical considerations not only facilitates the development of more reliable and ethically responsible BCI technologies but also fosters trust and acceptance among users and stakeholders. By prioritizing ethical principles and responsible practices, the BCI community can pave the way for the ethical and equitable deployment of AI-driven neurotechnologies in diverse applications, from healthcare to assistive technology and beyond.

Conclusion

In the world of neuroscience and technology, combining Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) with AI represents a remarkable convergence of human ingenuity and technological innovation. It's like bringing together our brains and technology to do amazing things. But as we explore this new frontier, it's important to remember to do it right.

We need to make sure we are using AI and BCI in ways that respect people's privacy and rights. By working together and being open about what we're doing, we can ensure that the benefits of BCI technology are accessible to all while safeguarding the privacy and dignity of individuals.

Capturing a biosignal is only the beginning. The real challenge starts once those tiny electrical fluctuations from your brain, heart, or muscles are recorded. What do they mean? How do we clean, interpret, and translate them into something both the machine and eventually we can understand? In this blog, we move beyond sensors to the invisible layer of algorithms and analysis that turns raw biosignal data into insight. From filtering and feature extraction to machine learning and real-time interpretation, this is how your body’s electrical language becomes readable.

Every heartbeat, every blink, every neural spark produces a complex trace of electrical or mechanical activity. These traces known collectively as biosignals are the raw currency of human-body intelligence. But in their raw form they’re noisy, dynamic, and difficult to interpret.

The transformation from raw sensor output to interpreted understanding is what we call biosignal processing. It’s the foundation of modern neuro- and bio-technology, enabling everything from wearable health devices to brain-computer interfaces (BCIs).

The Journey: From Raw Signal to Insight

When a biosignal sensor records, it captures a continuous stream of data—voltage fluctuations (in EEG, ECG, EMG), optical intensity changes, or pressure variations.

But that stream is messy. It includes baseline drift, motion artefacts, impedance shifts as electrodes dry, physiological artefacts (eye blinks, swallowing, jaw tension), and environmental noise (mains hum, electromagnetic interference).

Processing converts this noise-ridden stream into usable information, brain rhythms, cardiac cycles, muscle commands, or stress patterns.

Stage 1: Pre-processing — Cleaning the Signal

Before we can make sense of the body’s signals, we must remove the noise.

- Filtering: Band-pass filters (typically 0.5–45 Hz for EEG) remove slow drift and high-frequency interference; notch filters suppress 50/60 Hz mains hum.

- Artifact removal: Independent Component Analysis (ICA) and regression remain the most common methods for removing eye-blink (EOG) and muscle (EMG) artefacts, though hybrid and deep learning–based techniques are becoming more popular for automated denoising.

- Segmentation / epoching: Continuous biosignals are divided into stable time segments—beat-based for ECG or fixed/event-locked windows for EEG (e.g., 250 ms–1 s)—to capture temporal and spectral features more reliably.

- Normalization & baseline correction: Normalization rescales signal amplitudes across channels or subjects, while baseline correction removes constant offsets or drift to align signals to a common reference.

Think of this stage as cleaning a lens: if you don’t remove the smudges, everything you see through it will be distorted.

Stage 2: Feature Extraction — Finding the Patterns

Once the signal is clean, we quantify its characteristics, features that encode physiological or cognitive states.

Physiological Grounding

- EEG: Arises from synchronized postsynaptic currents in cortical pyramidal neurons.

- EMG: Records summed action potentials from contracting muscle fibers.

- ECG: Reflects rhythmic depolarization of cardiac pacemaker (SA node) cells.

Time-domain Features

Mean, variance, RMS, and zero-crossing rate quantify signal amplitude and variability over time. In EMG, Mean Absolute Value (MAV) and Waveform Length (WL) reflect overall muscle activation and fatigue progression.

Frequency & Spectral Features

The power of each EEG band tends to vary systematically across mental states.

Time–Frequency & Non-Linear Features

Wavelet transforms or Empirical Mode Decomposition capture transient events. Entropy- and fractal-based measures reveal complexity, useful for fatigue or cognitive-load studies.

Spatial Features

For multi-channel EEG, spatial filters such as Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) isolate task-specific cortical sources.

Stage 3: Classification & Machine Learning — Teaching Machines to Read the Body

After feature extraction, machine-learning models map those features to outcomes: focused vs fatigued, gesture A vs gesture B, normal vs arrhythmic.

- Classical ML: SVM, LDA, Random Forest , effective for curated features.

- Deep Learning: CNNs, LSTMs, Graph CNNs , learn directly from raw or minimally processed data.

- Transfer Learning: Improves cross-subject performance by adapting pretrained networks.

- Edge Inference: Deploying compact models (TinyML, quantized CNNs) on embedded hardware to achieve < 10 ms latency.

This is where raw physiology becomes actionable intelligence.

Interpreting Results — Making Sense of the Numbers

A robust pipeline delivers meaning, not just data:

- Detecting stress or fatigue for adaptive feedback.

- Translating EEG patterns into commands for prosthetics or interfaces.

- Monitoring ECG spectral shifts to flag early arrhythmias.

- Quantifying EMG coordination for rehabilitation or athletic optimization.

Performance hinges on accuracy, latency, robustness, and interpretability, especially when outcomes influence safety-critical systems.

Challenges and Future Directions

Technical: Inter-subject variability, electrode drift, real-world noise, and limited labeled datasets still constrain accuracy.

Ethical / Explainability: As algorithms mediate more decisions, transparency and consent are non-negotiable.

Multimodal Fusion: Combining EEG + EMG + ECG data improves reliability but raises synchronization and power-processing challenges.

Edge AI & Context Awareness: The next frontier is continuous, low-latency interpretation that adapts to user state and environment in real time.

Final Thought

Capturing a biosignal is only half the story. What truly powers next-gen neurotech and human-aware systems is turning that signal into sense. From electrodes and photodiodes to filters and neural nets, each link in this chain brings us closer to devices that don’t just measure humans; they understand them.

Every thought, heartbeat, and muscle twitch leaves behind a signal, but how do we actually capture them? In this blog post, we explore the sensors that make biosignal measurement possible, from EEG and ECG electrodes to optical and biochemical interfaces, and what it takes to turn those signals into meaningful data.

When we think of sensors, we often imagine cameras, microphones, or temperature gauges. But some of the most fascinating sensors aren’t designed to measure the world, they’re designed to measure you.

These are biosignal sensors: tiny, precise, and increasingly powerful tools that decode the electrical whispers of your brain, heart, and muscles. They're the hidden layer enabling brain-computer interfaces, wearables, neurofeedback systems, and next-gen health diagnostics.

But how do they actually work? And what makes one sensor better than another?

Let’s break it down, from scalp to circuit board.

First, a Quick Recap: What Are Biosignals?

Biosignals are the body’s internal signals, electrical, optical, or chemical , that reflect brain activity, heart function, muscle movement, and more. If you’ve read our earlier post on biosignal types, you’ll know they’re the raw material for everything from brain-computer interfaces to biometric wearables.

In this blog, we shift focus to the devices and sensors that make it possible to detect these signals in the real world, and what it takes to do it well.

The Devices That Listen In: Biosignal Sensor Types

.webp)

A Closer Look: How These Sensors Work

1. EEG / ECG / EMG – Electrical Sensors

These measure voltage fluctuations at the skin surface, caused by underlying bioelectric activity.

It’s like trying to hear a whisper in a thunderstorm; brain and muscle signals are tiny, and will get buried under noise unless the electrodes make solid contact and the amplifier filters aggressively.

There are two key electrode types:

- Wet electrodes: Use conductive gel or Saline for better signal quality. Still the gold standard in labs.

- Dry electrodes: More practical for wearables but prone to motion artifacts and noise (due to higher electrode resistance).

Signal acquisition often involves differential recording and requires high common-mode rejection ratios (CMRR) to suppress environmental noise.

Fun Fact: Even blinking your eyes generates an EMG signal that can overwhelm EEG data. That’s why artifact rejection algorithms are critical in EEG-based systems.

2. Optical Sensors (PPG, fNIRS)

These use light to infer blood flow or oxygenation levels:

- PPG: Emits light into the skin and measures reflection, pulsatile blood flow alters absorption.

- fNIRS: Uses near-infrared light to differentiate oxygenated vs. deoxygenated hemoglobin in the cortex.

Example: Emerging wearable fNIRS systems like Kernel Flow and OpenBCI Galea are making brain oxygenation measurement accessible outside labs.

3. Galvanic Skin Response / EDA – Emotion’s Electrical Signature

GSR (also called electrodermal activity) sensors detect subtle changes in skin conductance caused by sweat gland activity, a direct output of sympathetic nervous system arousal. When you're stressed or emotionally engaged, your skin becomes more conductive, and GSR sensors pick that up.

These sensors apply a small voltage across two points on the skin and track resistance over time. They're widely used in emotion tracking, stress monitoring, and psychological research due to their simplicity and responsiveness.

Together, these sensors form the foundation of modern biosignal acquisition — but capturing clean signals isn’t just about what you use, it’s about how you use it.

How Signal Quality Is Preserved

Measurement is just step one; capturing clean, interpretable signals involves:

- Analog Front End (AFE): Amplifies low signals while rejecting noise.

- ADC: Converts continuous analog signals into digital data.

- Signal Conditioning: Filters out drift, DC offset, 50/60Hz noise.

- Artifact Removal: Eye blinks, jaw clenches, muscle twitches.

Hardware platforms like TI’s ADS1299 and Analog Devices’ MAX30003 are commonly used in EEG and ECG acquisition systems.

New Frontiers in Biosignal Measurement

- Textile Sensors: Smart clothing with embedded electrodes for long-term monitoring.

- Biochemical Sensors: Detect metabolites like lactate, glucose, or cortisol in sweat or saliva.

- Multimodal Systems: Combining EEG + EMG + IMU + PPG in unified setups to boost accuracy.

A recent study involving transradial amputees demonstrated that combining EEG and EMG signals via a transfer learning model increased classification accuracy by 2.5–4.3% compared to EEG-only models.

Other multimodal fusion approaches, such as combining EMG and force myography (FMG), have shown classification improvements of over 10% compared to EMG alone.

Why Should You Care?

Because how we measure determines what we understand, and what we can build.

Whether it's a mental wellness wearable, a prosthetic limb that responds to thought, or a personalized neurofeedback app, it all begins with signal integrity. Bad data means bad decisions. Good signals? They unlock new frontiers.

Final Thought

We’re entering an era where technology doesn’t just respond to clicks, it responds to cognition, physiology, and intent.

Biosignal sensors are the bridge. Understanding them isn’t just for engineers; it’s essential for anyone shaping the future of human-aware tech.

In our previous blog, we explored how biosignals serve as the body's internal language—electrical, mechanical, and chemical messages that allow us to understand and interface with our physiology. Among these, electrical biosignals are particularly important for understanding how our nervous system, muscles, and heart function in real time. In this article, we’ll take a closer look at three of the most widely used electrical biosignals—EEG, ECG, and EMG—and their growing role in neurotechnology, diagnostics, performance tracking, and human-computer interaction. If you're new to the concept of biosignals, you might want to check out our introductory blog for a foundational overview.

"The body is a machine, and we must understand its currents if we are to understand its functions."-Émil du Bois-Reymond, pioneer in electrophysiology.

Life, though rare in the universe, leaves behind unmistakable footprints—biosignals. These signals not only confirm the presence of life but also narrate what a living being is doing, feeling, or thinking. As technology advances, we are learning to listen to these whispers of biology. Whether it’s improving health, enhancing performance, or building Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs), understanding biosignals is key.

Among the most studied biosignals are:

- Electroencephalogram (EEG) – from the brain

- Electrocardiogram (ECG) – from the heart

- Electromyogram (EMG) – from muscles

- Galvanic Skin Response (GSR) – from skin conductance

These signals are foundational for biosignal processing, real-time monitoring, and interfacing the human body with machines. In this article we look at some of these biosignals and some fascinating stories behind them.

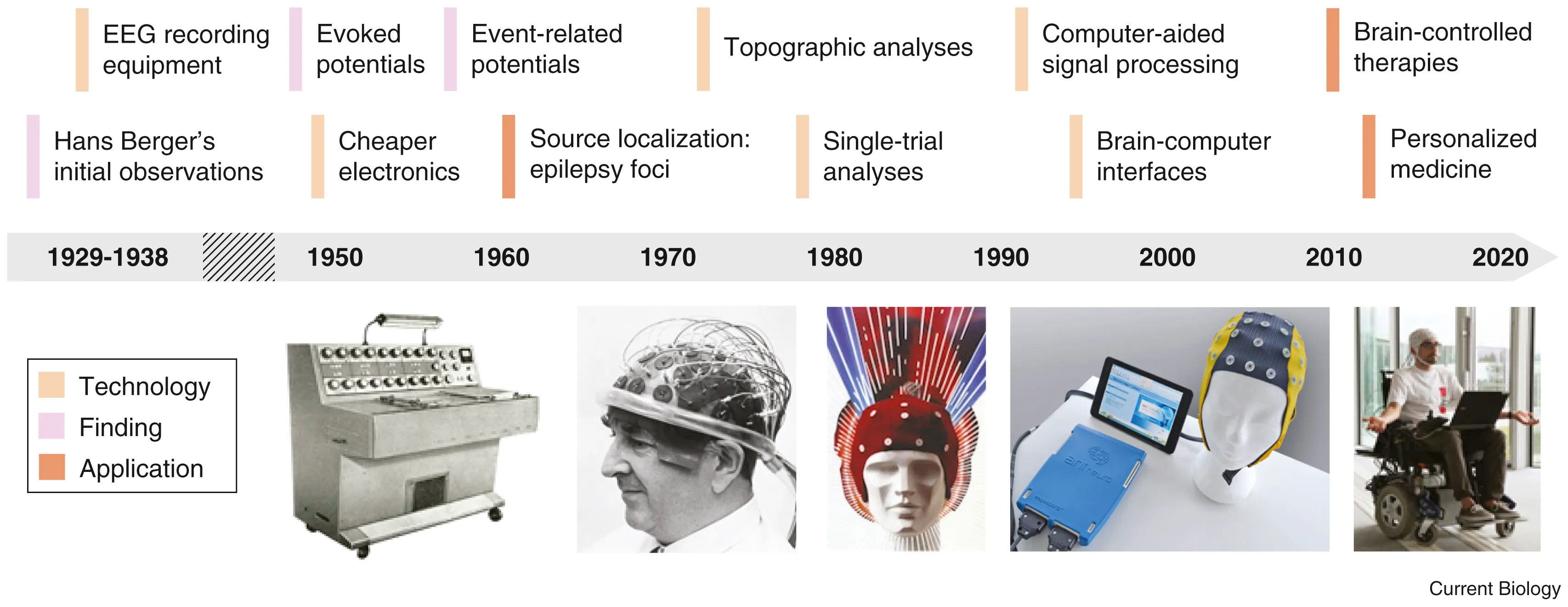

Electroencephalography (EEG): Listening to Brainwaves

In 1893, a 19 year old Hans Berger fell from a horse and had a near death experience. Little did he know that it would be a pivotal moment in the history of neurotechnology. The same day he received a telegram from his sister who was extremely concerned for him because she had a bad feeling. Hans Berger was convinced that this was due to the phenomenon of telepathy. After all, it was the age of radio waves, so why can’t there be “brain waves”? In his ensuing 30 year career telepathy was not established but in his pursuit, Berger became the first person to record brain waves.

When neurons fire together, they generate tiny electrical currents. These can be recorded using electrodes placed on the scalp (EEG), inside the skull (intracranial EEG), or directly on the brain (ElectroCorticogram). EEG signal processing is used not only to understand the brain’s rhythms but also in EEG-based BCI systems, allowing communication and control for people with paralysis. Event-Related Potentials (ERPs) and Local Field Potentials (LFPs) are specialized types of EEG signals that provide insights into how the brain responds to specific stimuli.

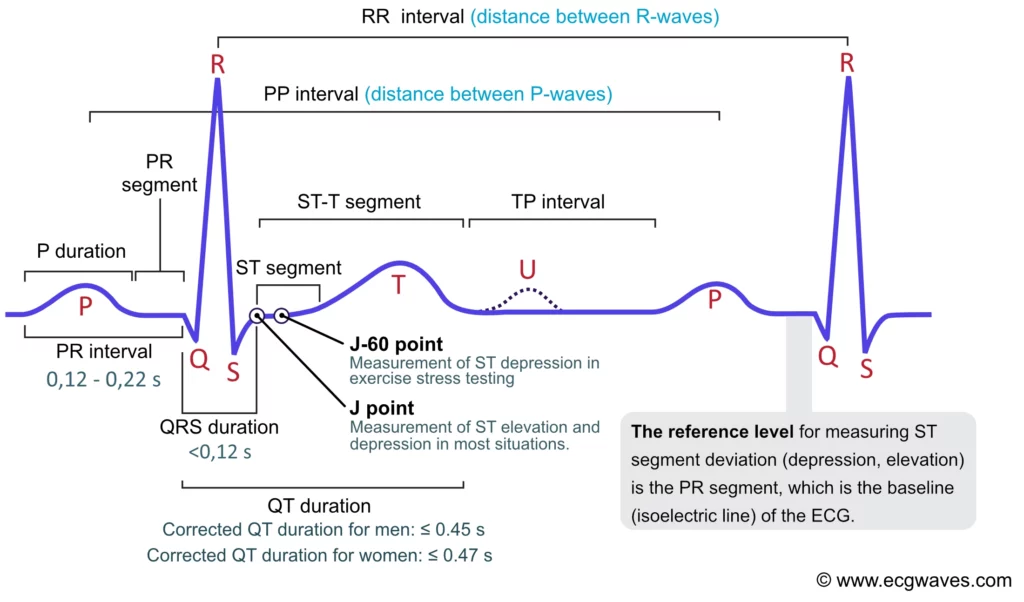

Electrocardiogram (ECG): The Rhythm of the Heart

The heart has its own internal clock which produces tiny electrical signals every time it beats. Each heartbeat starts with a small electrical impulse made by a special part of the heart called the sinoatrial (SA) node. This impulse spreads through the heart muscle and makes it contract, first the upper (atria) and then lower chambers (ventricles) – that’s what pumps blood. This process produces voltage changes, which can be recorded via electrodes on the skin.

This gives rise to the classic PQRST waveform, with each component representing a specific part of the heart’s cycle. Modern wearables and medical devices use ECG signal analysis to monitor heart health in real time.

Fun fact: The waveform starts with “P” because Willem Einthoven left room for earlier letters—just in case future scientists discovered pre-P waves! So, thanks to a cautious scientist, we have the quirky naming system we still follow today.

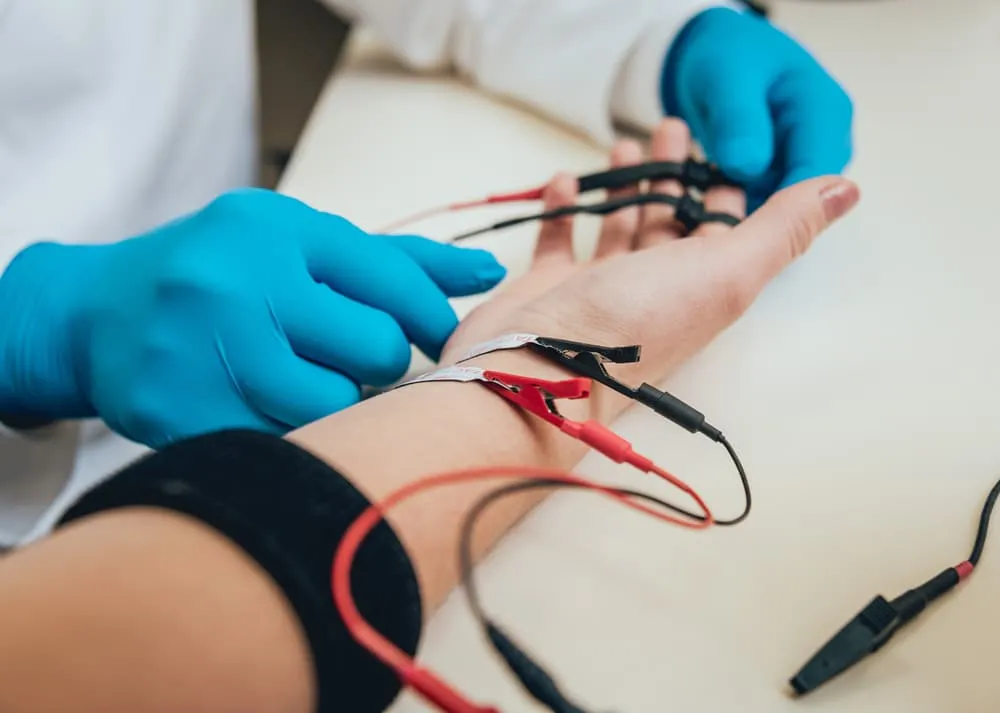

Electromyography (EMG): The Language of Movement

When we perform any kind of movement - lifting our arm, kicking our leg, smiling, blinking or even breathing- our brain sends electrical signals to our muscles telling them to contract. When these neurons, known as motor neurons fire they release electrical impulses that travel to the muscle, causing it to contract. This electrical impulse—called a motor unit action potential (MUAP)—is what we see as an EMG signal. So, every time we move, we are generating an EMG signal!

Medical Applications

Medically, EMG is used for monitoring muscle fatigue especially in rehabilitation settings and muscle recovery post-injury or surgery. This helps clinicians measure progress and optimize therapy. EMG can distinguish between voluntary and involuntary movements, making it useful in diagnosing neuromuscular disorders, assessing stroke recovery, spinal cord injuries, and motor control dysfunctions.

Performance and Sports Science

In sports science, EMG can tell us muscle-activation timing and quantify force output of muscle groups. These are important factors to measure performance improvement in any sport. The number of motor units recruited and the synergy between muscle groups, helps us capture “mind-muscle connection” and muscle memory. Such things which were previously spoken off in a figurative manner can be scientifically measured and quantified using EMG. By tracking these parameters we get a window into movement efficiency and athletic performance. EMG is also used for biofeedback training, enabling individuals to consciously correct poor movement habits or retrain specific muscles

Beyond medicine and sports, EMG is used for gesture recognition in AR/VR and gaming, silent speech detection via facial EMG, and next-gen prosthetics and wearable exosuits that respond to the user’s muscle signals. EMG can be used in brain-computer interfaces (BCIs), helping paralyzed individuals control digital devices or communicate through subtle muscle activity. EMG bridges the gap between physiology, behavior, and technology—making it a critical tool in healthcare, performance optimization, and human-machine interaction.

As biosignal processing becomes more refined and neurotech devices more accessible, we are moving toward a world where our body speaks—and machines understand. Whether it’s detecting the subtlest brainwaves, tracking a racing heart, or interpreting muscle commands, biosignals are becoming the foundation of the next digital revolution. One where technology doesn’t just respond, but understands.